By Jon: First published in Online Currents 2003 – 18(4): 10-12

In this series of 3 articles I first summarise the current state of the e-book market in general and then look at the situation for non-fiction e-books. I give some reasons why non-fiction books are not sharing in the rapid growth of fiction titles and examine several models for non-fiction e-book distribution: free downloads; paid downloads; paid distribution on CD or other media; and ‘library’ systems which sell access to texts but not the texts themselves.

Current trends

Two years ago the e-book market was in turmoil. A multitude of different platforms, formats, copy protection schemes and business models were struggling for market share and it was anybody’s guess what the outcome would be. Since then many of the contenders have disappeared and others have established themselves; although things are still unsettled it is possible to get a glimpse of a mature e-book market emerging.

Hardware

Dedicated reading devices appear to have little future, and the manufacturers continue to be their own worst enemies. After financial problems and a change of management GemStar released an ‘upgrade’ to its RocketBook system which prevents users from reading their own content. Faced with an enormous outcry, the company is planning to restore this facility late in 2003, but there may not be any readers left by then. Sales of Rocket-format e-books are reportedly dropping towards zero at many distribution sites. Meanwhile the quirky eBookMan series by Franklin was discontinued and can be picked up for bargain prices by enthusiasts.

It seems likely that e-books will become just one facility among many offered by general-purpose Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) and other portable computing devices. These continue to offer more features and better value for money. Typical models now include .MP3 music file playing capabilities and a colour screen. Some come with mobile phones, others with a digital camera and recording system. Memory cards have become cheaper, partly due to their widespread use in digital cameras; 128 Mb is a popular size and 256 Mb cards are available. (For comparison, a typical e-book is 400 Kb). Card reading and writing devices make it simpler and cheaper to transfer large files between a PDA and a PC without the need to plug the PDA into a connection or ‘cradle’.

The Palm Pilot remains the most popular PDA system and has been augmented by the Pilot Zire, an entry-level machine selling for less than $AU300. Other systems, however, especially the Sony Clié, are making inroads on what was once Palm’s virtual monopoly. More and better PDA software continues to appear, much of it written by volunteers and distributed for free. As well as e-book display programs there is an abundance of business software and games now available for almost all PDAs.

The recent arrival of tablet PCs may also have an impact on the PDA market when they drop in price and improve in usability.

Display programs and document formats

Display programs for PDAs are becoming more versatile. The popular MobiPocket Reader program (www.mobipocket.com), now available for many PDAs, is a typical example. When switched on it displays a library of files including text, .PDB and .HTML files. It can set fonts to one of three sizes and allows the user to go to a specified page or a bookmark. It also responds to hyperlinks in HTML files. When you switch off it remembers your location in the text. A paid Pro version includes an option to rotate the screen to landscape mode. Meanwhile display programs that are ‘locked in’ to one format, like the Microsoft Reader (www.microsoft.com) and the Franklin Reader (www.franklin.com), appear to be losing ground, especially as the Microsoft Reader for PDAs will only run on pricey top-of-the-range devices.

Desktop and laptop PC display programs for e-books are also improving. A new version of Microsoft Reader is available and Adobe have revised their Acrobat Reader to allow text to wrap to the screen size, making it more user-friendly for smaller screens.

Most major e-book distributors now offer a variety of formats – for instance, Baen Books offers HTML, RTF, .LIT, .PDB and Rocket files – and some have experimented with ‘while-you-wait’ conversion before download. Adobe Acrobat is not yet available for PDAs, so .PDF files are not an option here. HTML is still a contender, and plain text remains as the basis of the large Project Gutenberg collection.

Copy protection – usually referred to nowadays as Digital Rights Management (DRM) – is losing ground. Users are making it known that they don’t want the bother of downloading texts that require passwords and de-encryption and can’t be copied to other platforms. One often-heard comment is: ‘what if this copy gets corrupted and your company isn’t there any more?’ Despite US laws that may make it illegal even to discuss how copy protection might be circumvented, most copy protection schemes have been broken and ways have been found to extract plain text from a variety of supposedly secure formats including Microsoft’s .LIT files. One successful e-book fiction publisher, Jim Baen, has spoken out publicly against DRM; seehttp://www.baen.com/library.

E-book creation software

Would-be e-book authors now have a range of creation packages available. Most of these start with HTML files as their input format and compile these into chapters in a single book file. To implement copy protection on an e-book usually requires a paid-for ‘Pro’ package, but many other packages are available as freeware including the MobiPocket Publisher.

Distribution

Public domain sources of texts continue to grow, most of them contributed by volunteer scanners and proofreaders. Project Gutenberg (www.pg.promo.net) is growing exponentially. Thanks to a distributed proofreading system (http://texts01.archive.org/dp/), volunteers can now log on and proofread a few pages at a time via the Web: input is currently averaging between 3,000 and 4,000 pages per day. Blackmask (www.blackmask.com) has successfully collected thousands of works of popular literature from the public domain and is offering 10,000 books on CD for $US25 – the equivalent of four books for one cent. A similar project, Samizdat (www.samizdat.com), is discussed in detail in the third article in this series.

The number of e-books distributed has increased rapidly – from a few hundred into many thousands – although the revenue effect of this has been offset by a decline in prices. Distributors are now often using ‘discounts’ and ‘special deals’ to shave dollars off their original prices. Some publishers are giving away a portion of a book, or one book out of a series, in the hope of hooking a reader in to buy the rest. Nonetheless, there are still distributors who are charging more for an electronic book than the RRP of the paper version.

Vanity publishing has become an online phenomenon; many sites will list and sell any and every text submitted to them – for a fee. A brief examination of these titles and their contents shows that they are unlikely to have an impact on the reading public; in fact, vanity publishers’ sites and advertisements often show the same poor grasp of written English as their clients’ books. Slightly more significant are the self-published niche books, often taking the form of How To… manuals, distributed in ones and twos from their own websites by the authors; some of these are described in the next article.

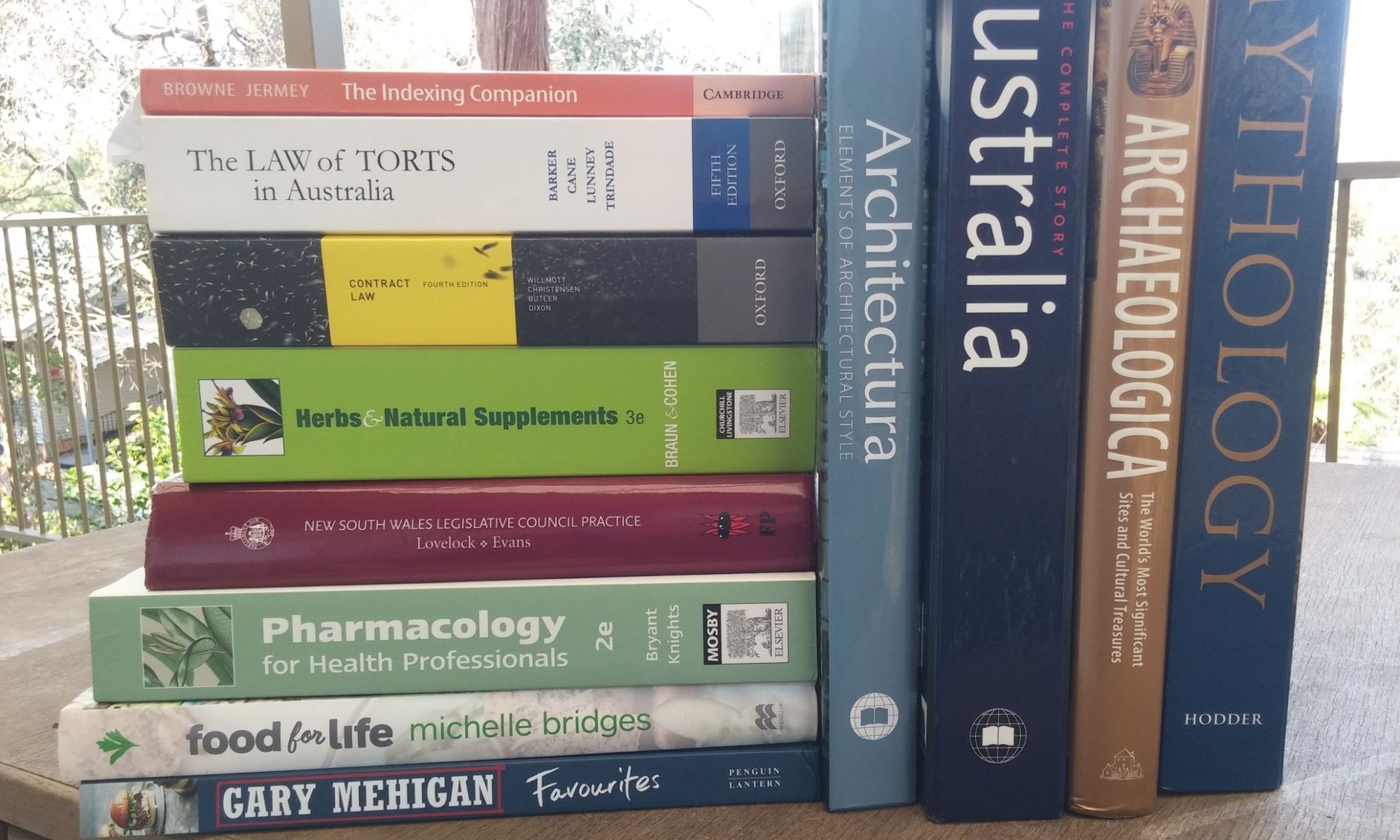

Baen Books vs Cybereditions: spot the non-fiction distributor!

Fiction vs non-fiction

Fiction is the Cinderella of the e-book story; non-fiction an Ugly Sister. Large fiction sites like Fictionwise (www.fictionwise.com) and Baen Books (www.baen.com) offer a choice of hundreds of books while non-fiction distributors like Cybereditions (www.cybereditions.com) have a couple of dozen at most. The Internet clearly has a much smaller ratio of non-fiction to fiction books than a typical public library or bookstore. Non-fiction e-books that do appear on the Internet tend to be books for ‘reading through’, like biographies and travel articles, rather than scholarly reference books for ‘looking up’.

Some of the reasons for this are:

- Fiction books are typically all text and as such are relatively easy to scan, proofread, store and convert to a variety of different formats. Non-fiction books often contain non-text material like photographs, sidebars, worked exercises and tables. These are expensive to convert accurately to electronic formats, and their large size limits the book’s downloadability. The same applies to scholarly apparatus like indexes and footnotes, which need to be extensively recast for an e-book version. Even if these are included they may be rendered useless by the conversion.

- A major part of the market for reference books is sales to libraries, but most libraries are not yet geared up for e-book purchasing and use.

- Reference books are usually expected to have a long life, but the rapid turnover of distributors and formats in the e-book market make it difficult to be sure that an e-book purchased today may still be usable in, say, two years’ time.

Underlying these concerns is a perception that the e-book format is inappropriate for reference material anyway, and that this is better provided through an open, updatable hyperlinked structure like that of the World Wide Web. The rapid success of electronic encyclopaedias on CD, and the resulting collapse of the printed encyclopaedia market, shows how effective the right combination of information, price and format could be. Now CD encyclopaedias are themselves at risk as people turn directly to the Web for ‘hard’ information. What we may see in the future is an increasing divergence between books for ‘reading’ and websites for ‘looking up’, with specific websites (and to a lesser extent CDs) taking over the function of reference books. Where the same material is used for reading through and looking up, there may be a split between versions, with extra charges applying for the indexed, updated scholarly version of a text.

However, there are still many non-fiction e-books available. In the next article in this series I will discuss their distribution through free or paid downloading.